Guest Article: Why No HOFers From '84 Tigers?

I normally don't post guest articles---in fact, I don't know that I ever have on this blog---but I thought I'd share this one.

It's from Chris Jaffe of the Hardball Times, and it speaks to the lack of Hall of Fame love doled out to members of the 1984 Detroit Tigers, a World Series-winning team without any HOFers on it, which is highly unusual.

Take it away, Chris!

*****************************************************

March 05, 2012

A few weeks ago, I wrote a column looking at how players on championship teams fare in Hall of Fame voting. Every World Series-winning team through 1980 has at least one player from its squad in the Hall of Fame, with the 1940 Reds having the longest wait, as the team’s catcher, Ernie Lombardi, didn’t get in until 1986, 46 years after their victory.

Since 1981, many championship clubs either have a Hall of Famer or will almost certainly get one once their stars become eligible for Cooperstown. The main exceptions are either clubs where their star players are caught up in the steroids controversy (the 1997 Marlins had 500-homer guy Gary Sheffield, for instance), or clubs that were the best in the postseason but not necessarily the regular season (such as the 2002 wild card Angels).

That said, there’s one team that stands out as an exception. They dominated the season they were in, had several high profile stars and perennial All-Stars, and yet, despite having many players eligible for Cooperstown for many years, have not seen a single player receive the game’s highest honor.

That club is the 1984 Tigers.

On the one hand, the Tigers share something in common with the likes of the 2002 Angels and 1997 Marlins: They all won precisely one title.

True, but the Tigers were quite a bit more than a one-title wonder. It came in the midst of 11 consecutive winning seasons for the Tigers. During that stretch, they also won the 1987 AL East title, only to lose in a major upset in the ALCS to a clearly inferior Twins team. From 1983-88, a full six-year span, the Tigers were the winningest team in the American League, posting a 553-418 (.570) record.

Most memorably, they were an absolute dynamo in their 1984 championship season. They topped the league in most runs scored and fewest runs allowed; the only AL team to do that from 1972-94. (If you're curious, it's the 1971 O's and 1995 Indians at either end.) As a result, they went 104-58.

That 104-58 mark might actually undersell how good the Tigers were. They famously got off to the greatest start ever, becoming the first team to begin the year 35-5.

Yet, the mid-1980s Tigers can’t get into Cooperstown. Twenty-eight years after they won it all, they still haven’t had a single member enter Cooperstown. That’s the third-longest stretch by any championship team in the last 100 years.

Let’s look at some of their best players and main Cooperstown candidates to see why none is yet in.

Lemon is pretty clearly a Hall of Very Gooder. He could play, but he didn’t last long enough to amass Hall-worthy career stats, and his peak wasn’t bright enough to get in for his best seasons. But Lemon could play.

In his prime (which mostly came with the White Sox), he could hit .300 with midrange power and plenty of doubles. Lemon also played good defense in center field. If you go by WAR (and you don’t necessarily have to), his career value of 49.9 WAR is equal to Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio and superior to many other Hall of Famers.

But while you can compare Lemon to a lot of Hall of Famers, but you can also compare him to a lot of non-Hall of Famers.

Another clear Hall of Very Gooder. Gibson had a nice sustained prime from 1984-88 but, hampered by injuries, he didn’t do that much outside of that period. He played only 1,635 games in his entire career. If you’re going to have that short a career, you need to do more than hit .268 with 255 homers.

He’s also one of the most prominent players of the last 70 years to never garner an All-Star selection.

Formerly a successful outfielder, Gibson is currently a successful manager.

Here’s a nice stump-the-band trivia question for you: Which member of the 1980s Tigers had the most career All-Star game selections? Lance Parrish, with eight.

Parrish was the annual pick to catch for the AL in the 1980s, but in part that serves as an indictment of the catchers of the era. In 1984, for example, he was the starting catcher for the AL despite hitting just .237 on the year. Okay, fine, he also had 33 homers, but his on-base percentage was .287. Four years later, he made the All-Star game as a Phillie despite batting .215 on the year.

Parrish was a good player in his prime, and he was one of the best power-hitting catchers of the day, routinely hitting in the upper 20s or lower 30s in homers. Back then, those numbers were impressive.

But ultimately, he’s another Hall of Very Gooder. Parrish, Gibson, and Lemon were extremely solid players, but none was brilliant enough in his prime or lasted long enough to become a serious Hall of Fame candidate.

Here’s where the Cooperstown cases start getting better. That said, it’s easy to forget Evans was on this team. While many others spent the better part (or all) of their careers in Detroit, Evans was there for merely five seasons.

This was the first and arguably least of those seasons, as Evans batted .232 with 16 homers as the club’s designated hitter. He actually had a good OBP thanks to a lot of walks but was about average on the year.

Yeah, but over the whole of Evans' career, he was damn good. Bill James once used Evans as an example of a player who is easy to underestimate. He lasted a long time but never had that obvious great peak that draws attention. He wasn’t superlative at any one aspect of the game, but could do various things well (slug, get on base, and Evans even fielded well enough to last a long time at third).

In the end, Evans snuck up on people. He ended his career ranked 21st in homers, right between Billy Williams and Duke Snider. He retired eighth all-time in walks with 1,605. As a result of all those base on balls, Evans finished his career with a better OBP than Roberto Clemente despite the fact that Clemente had a 69-point edge in batting average: .317 to .248.

Evans never had a chance for Cooperstown, though. The guy has a case if you take a deep sabermetric approach, but that approach has never been the way into Cooperstown. He’s a player with a .248 average who made only two All-Star teams in his career. Evans received only eight votes when he hit the ballot, not nearly enough to maintain his spot for Cooperstown’s consideration.

Whitaker has a strong argument for Cooperstown. He was a star in his prime who remained an effective player for a very long time.

According to Similarity Scores, Whitaker’s most similar player is Ryne Sandberg. Both were annual All-Star second baseman for the two leagues in the 1980s. Each had nice power for the position. Both belted over 400 doubles and retired among the all-time leaders in homers at second base. Sandberg had more power and stolen bases, but Whitaker tops him in walks and OBP. Sandberg has the edge in OPS (795 to 789), but Whitaker is ahead in OPS+ (116 to 114).

Ultimately, they are very comparable. As similar as they are, there is one key difference. Sandberg crusied into Cooperstown in his third year on the ballot while Whitaker fell under five percent in his first try and never got a second glance from the BBWAA.

Yep. Lou Whitaker got 2.9 percent of the vote in the 2001. Mark Belanger got 3.7 percent in his only try. Joe Carter got 3.8 percent. Mark Grace and Andres Galarraga both topped four percent. So did Bob Boone and Manny Mota.

But Whitaker flopped after his first year. You can even make a stronger case for Whitaker than made above, too. According to WAR, he’s the seventh-best second baseman of all-time, better than Sandberg, Roberto Alomar or Craig Biggio, among others.

In this case, WAR is a bit out there compared to many other stats, but if you just compare him to most Hall of Fame second basemen, Whitaker clearly fits in. In his New Historical Abstract, Bill James rated him the 13th-best second sacker ever, behind 10 Hall of Famers, Craig Biggio (who will go in), and Bobby Grich (whom James ranks 12th).

Yet Whitaker didn’t even get five percent. Why not? Well, first he lacked that single “Wow!” season a la Sandberg’s 1984 campaign. While Whitaker was an annual All-Star in his prime, that only lasted five seasons. Selections to the All-Star game in five different years puts put Whitaker even with Chase Utley and Gil McDougald. That reflects popular thought about Whitaker in his prime.

Whitaker, like Evans, is a guy whose career value sneaks up on you. He aged very strangely and effectively. When Whitaker first came up as a young player, his batting average came and went, and he had no power. By his mid-20s, he developed a good average and moderate power. Once he found his stroke, he never really lost it.

Thus, he batted .293 with 14 homers in just 84 games at age 38 in his final season. The year before, he batted .301 with 12 homers in 93 games. He was just a pretty good player for a bizarrely long time after his prime.

Also, his usage hurts his popular perception. After 1987, he played over 140 games only once. Manager Sparky Anderson generally sat the lefty-hitting Whitaker against southpaws, so Whitaker was something of a platoon player for nearly a decade. He played in four-fifths of his team’s games, but that still dings his popular perception.

Also, because he lasted so long in this role, memories of his prime fizzled. Instead of benefiting from both parts of his career, they each hurt his candidacy. It’s not fair, but it’s apparently what happened. Whitaker belongs in, and hopefully he’ll go in, but for now he isn’t in.

Shortstop Alan Trammell has the best statistical case for enshrinement of the 1980s Tigers.

Want a player with an impressive peak? Check out Trammell’s 1987. He batted .343 with 28 homers and 21 stolen bases (versus only two caught stealings) while playing the diamond’s most important defensive position. He should’ve won the MVP Award that year, but finished second to George Bell in one of the worst votes in baseball awards history.

That was Trammell’s best year, for sure, but he frequently batted over .300 with decent mid-range power throughout his prime. From 1983-88, he batted .303 with 105 homers.

Trammell was an incredibly well-rounded player with no real holes in his game. He had a nice average and decent power, stole over 200 bases in his career, played solid defense, drew his share of walks and was hard to strike out. He wasn’t great at every aspect of the game, but he wasn’t bad at any of them.

Finally, Trammell lasted long enough to tally impressive career numbers. He got over 2,000 hits, including over 600 for extra bases. His 110 OPS+ isn’t terribly impressive on its own, but it’s damn good for a long-lasting shortstop.

Unlike every other player mentioned so far, Trammell didn’t fall off the BBWAA ballot after his first year. He recently completed his 11th turn on the BBWAA ballot and received an all-time personal best of 36.8 percent of the vote. He’s very unlikely ever to go in via the BBWAA but has a good shot with the VC. Generally, good candidates who did that well with the BBWAA get elected by the VC.

He should’ve gone in earlier, but Trammell was always overshadowed by Cal Ripken Jr. While Ripken had 19 consecutive All-Star Game selections, Trammell had only six. Five times, Trammell backed up Ripken in the All-Star Game. The sixth time he was a reserve for Bucky Dent.

As far as I can figure, Trammell is the best position player of the All-Star Game era (1933-onward) never to start in it. (Oddly enough, one of his best competitors for this title is his old teammate, Evans).

The interesting thing for Trammell is how recent the boom in his Hall support has been. He remained stuck at 13-18 percent for eight years but has gone up to 22, 24, and 36 percent ever since.

My hunch is the arrival of Barry Larkin helps Trammell. Normally,a similar player hurts as he competes for votes, but Trammell wasn’t getting that many votes anyway and,more importantly,not only was Larkin widely perceived as a Hall of Famer, but he a clearly similar career to Trammell.

Hopefully Trammell will get in, but for now he isn’t.

Trammell: Currently a bench coach for his old teammate, Kirk Gibson.

And now for the bizarre, ironic joke in the Tigers' Cooperstown drought: The man who will end it is maybe the fifth- or sixth-best candidate from the 1984 world champions.

Jack Morris was durable. He was damn durable, we have to give him that. And he picked the greatest time possible to hurl his greatest game ever, leading the Twins to a Game Seven, 1-0 10-inning win over the Braves in the 1991 Fall Classic.

But a Hall of Famer? Morris won a lot of games, but that’s in part because he had tremendous aid from his teammates. Those Tigers could hit, and in their prime they also were great at converting batted balls into outs. Teams managed by Sparky Anderson rarely won with great pitching. In Cincinnati and Detroit, he just needed pitchers not to lose so the hitters could win.

Thus, Morris could post 254 wins despite a 3.90 career ERA. He retired with the worst ERA of any 250-game winner. Jamie Moyer has since “surpassed” him, but at least Moyer played in a higher-scoring era, and no one seriously considers him a Hall of Famer.

Morris will go in, though. He’s now well over 60 percent of the vote, and even if he can’t get in via the BBWAA, he’ll go in as soon as the VC gets their hands on him. The Hall loves pitchers with big win totals, and Morris (of course) won more games in the 1980s than anyone.

From the arrival of Evans in 1984 until the departure of Parrish after the 1986 seasons, there were 33 games in which Lemon, Gibson, Evans, Parrish, Whitaker, Trammell, and Morris all appeared in the starting lineup together. The Tigers went 23-10 (.697) in those games. That works out to a 113-49 mark over a full season.

For comparison's sake, in Morris' remaining 72 starts from 1984-86, the Tigers went 43-29 (.597), which is a 97-65 pace. That isn't too much worse than their record with all seven, but in those 72 games you normally had four or five of the star position players in the starting lineup.

One final note. While no player is in Cooperstown from the 1984 Tigers, the team hasn’t been fully skunked by the Hall. Manager Sparky Anderson is in. That makes sense, as he won five pennants and two world titles before ending his career ranked third in managerial wins.

Also, a lot of the world champion squads without any players in Cooperstown had a very well-regarded manager. That makes sense. Only one pre-1984 world champion has no players in Cooperstown: the 1981 Dodgers. Their manager, of course, was Hall of Famer Tommy Lasorda.

Since 1984, the two teams with arguably the worst odds of getting a player into Cooperstown are the 1997 Marlins and 2002 Angels. Their managers, Jim Leyland and Mike Scioscia, respectively, each could make it, however.

So, the Tigers are sort of represented, but they should have some players enshrined as well as their skipper. The issue for Detroit getting its guys into Cooperstown is that they were unusually deep with high-quality position players. These players were either not quite good enough or were underrated when they played, or both.

The oddity is that the overall quality of these many high-quality position players might end up pushing a pitcher into Cooperstown who isn’t as good a candidate as many of them. But at least there will be a 1984 Tiger in Cooperstown. Ideally, Trammell and Whitaker will eventually join Morris there.

History instructor by day, statnerd by night, Chris Jaffe leads one of the most exciting double lives imaginable; with the exception of every other double life possible to imagine. Despite his lack of comic-book-hero-worthiness, Chris enjoys farting around with this stuff. His new book, Evaluating Baseball's Managers is available for order. Chris welcomes responses to his articles via e-mail.

It's from Chris Jaffe of the Hardball Times, and it speaks to the lack of Hall of Fame love doled out to members of the 1984 Detroit Tigers, a World Series-winning team without any HOFers on it, which is highly unusual.

Take it away, Chris!

*****************************************************

The Detroit-Cooperstown non-connection

by Chris JaffeMarch 05, 2012

A few weeks ago, I wrote a column looking at how players on championship teams fare in Hall of Fame voting. Every World Series-winning team through 1980 has at least one player from its squad in the Hall of Fame, with the 1940 Reds having the longest wait, as the team’s catcher, Ernie Lombardi, didn’t get in until 1986, 46 years after their victory.

Since 1981, many championship clubs either have a Hall of Famer or will almost certainly get one once their stars become eligible for Cooperstown. The main exceptions are either clubs where their star players are caught up in the steroids controversy (the 1997 Marlins had 500-homer guy Gary Sheffield, for instance), or clubs that were the best in the postseason but not necessarily the regular season (such as the 2002 wild card Angels).

That said, there’s one team that stands out as an exception. They dominated the season they were in, had several high profile stars and perennial All-Stars, and yet, despite having many players eligible for Cooperstown for many years, have not seen a single player receive the game’s highest honor.

That club is the 1984 Tigers.

The greatness of the Tigers

On the one hand, the Tigers share something in common with the likes of the 2002 Angels and 1997 Marlins: They all won precisely one title.

True, but the Tigers were quite a bit more than a one-title wonder. It came in the midst of 11 consecutive winning seasons for the Tigers. During that stretch, they also won the 1987 AL East title, only to lose in a major upset in the ALCS to a clearly inferior Twins team. From 1983-88, a full six-year span, the Tigers were the winningest team in the American League, posting a 553-418 (.570) record.

Most memorably, they were an absolute dynamo in their 1984 championship season. They topped the league in most runs scored and fewest runs allowed; the only AL team to do that from 1972-94. (If you're curious, it's the 1971 O's and 1995 Indians at either end.) As a result, they went 104-58.

That 104-58 mark might actually undersell how good the Tigers were. They famously got off to the greatest start ever, becoming the first team to begin the year 35-5.

Yet, the mid-1980s Tigers can’t get into Cooperstown. Twenty-eight years after they won it all, they still haven’t had a single member enter Cooperstown. That’s the third-longest stretch by any championship team in the last 100 years.

Let’s look at some of their best players and main Cooperstown candidates to see why none is yet in.

Chet Lemon

Lemon is pretty clearly a Hall of Very Gooder. He could play, but he didn’t last long enough to amass Hall-worthy career stats, and his peak wasn’t bright enough to get in for his best seasons. But Lemon could play.

In his prime (which mostly came with the White Sox), he could hit .300 with midrange power and plenty of doubles. Lemon also played good defense in center field. If you go by WAR (and you don’t necessarily have to), his career value of 49.9 WAR is equal to Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio and superior to many other Hall of Famers.

But while you can compare Lemon to a lot of Hall of Famers, but you can also compare him to a lot of non-Hall of Famers.

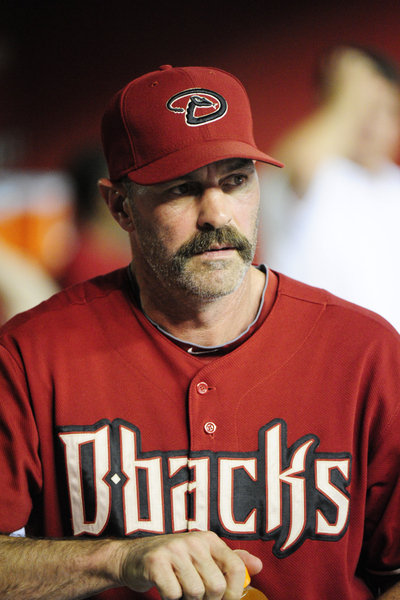

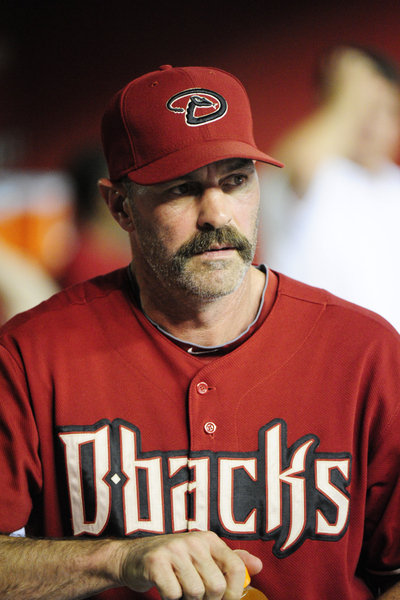

Kirk Gibson

Another clear Hall of Very Gooder. Gibson had a nice sustained prime from 1984-88 but, hampered by injuries, he didn’t do that much outside of that period. He played only 1,635 games in his entire career. If you’re going to have that short a career, you need to do more than hit .268 with 255 homers.

He’s also one of the most prominent players of the last 70 years to never garner an All-Star selection.

Formerly a successful outfielder, Gibson is currently a successful manager.

Lance Parrish

Here’s a nice stump-the-band trivia question for you: Which member of the 1980s Tigers had the most career All-Star game selections? Lance Parrish, with eight.

Parrish was the annual pick to catch for the AL in the 1980s, but in part that serves as an indictment of the catchers of the era. In 1984, for example, he was the starting catcher for the AL despite hitting just .237 on the year. Okay, fine, he also had 33 homers, but his on-base percentage was .287. Four years later, he made the All-Star game as a Phillie despite batting .215 on the year.

Parrish was a good player in his prime, and he was one of the best power-hitting catchers of the day, routinely hitting in the upper 20s or lower 30s in homers. Back then, those numbers were impressive.

But ultimately, he’s another Hall of Very Gooder. Parrish, Gibson, and Lemon were extremely solid players, but none was brilliant enough in his prime or lasted long enough to become a serious Hall of Fame candidate.

Darrell Evans

Here’s where the Cooperstown cases start getting better. That said, it’s easy to forget Evans was on this team. While many others spent the better part (or all) of their careers in Detroit, Evans was there for merely five seasons.

This was the first and arguably least of those seasons, as Evans batted .232 with 16 homers as the club’s designated hitter. He actually had a good OBP thanks to a lot of walks but was about average on the year.

Yeah, but over the whole of Evans' career, he was damn good. Bill James once used Evans as an example of a player who is easy to underestimate. He lasted a long time but never had that obvious great peak that draws attention. He wasn’t superlative at any one aspect of the game, but could do various things well (slug, get on base, and Evans even fielded well enough to last a long time at third).

In the end, Evans snuck up on people. He ended his career ranked 21st in homers, right between Billy Williams and Duke Snider. He retired eighth all-time in walks with 1,605. As a result of all those base on balls, Evans finished his career with a better OBP than Roberto Clemente despite the fact that Clemente had a 69-point edge in batting average: .317 to .248.

Evans never had a chance for Cooperstown, though. The guy has a case if you take a deep sabermetric approach, but that approach has never been the way into Cooperstown. He’s a player with a .248 average who made only two All-Star teams in his career. Evans received only eight votes when he hit the ballot, not nearly enough to maintain his spot for Cooperstown’s consideration.

Lou Whitaker

Whitaker has a strong argument for Cooperstown. He was a star in his prime who remained an effective player for a very long time.

According to Similarity Scores, Whitaker’s most similar player is Ryne Sandberg. Both were annual All-Star second baseman for the two leagues in the 1980s. Each had nice power for the position. Both belted over 400 doubles and retired among the all-time leaders in homers at second base. Sandberg had more power and stolen bases, but Whitaker tops him in walks and OBP. Sandberg has the edge in OPS (795 to 789), but Whitaker is ahead in OPS+ (116 to 114).

Ultimately, they are very comparable. As similar as they are, there is one key difference. Sandberg crusied into Cooperstown in his third year on the ballot while Whitaker fell under five percent in his first try and never got a second glance from the BBWAA.

Yep. Lou Whitaker got 2.9 percent of the vote in the 2001. Mark Belanger got 3.7 percent in his only try. Joe Carter got 3.8 percent. Mark Grace and Andres Galarraga both topped four percent. So did Bob Boone and Manny Mota.

But Whitaker flopped after his first year. You can even make a stronger case for Whitaker than made above, too. According to WAR, he’s the seventh-best second baseman of all-time, better than Sandberg, Roberto Alomar or Craig Biggio, among others.

In this case, WAR is a bit out there compared to many other stats, but if you just compare him to most Hall of Fame second basemen, Whitaker clearly fits in. In his New Historical Abstract, Bill James rated him the 13th-best second sacker ever, behind 10 Hall of Famers, Craig Biggio (who will go in), and Bobby Grich (whom James ranks 12th).

Yet Whitaker didn’t even get five percent. Why not? Well, first he lacked that single “Wow!” season a la Sandberg’s 1984 campaign. While Whitaker was an annual All-Star in his prime, that only lasted five seasons. Selections to the All-Star game in five different years puts put Whitaker even with Chase Utley and Gil McDougald. That reflects popular thought about Whitaker in his prime.

Whitaker, like Evans, is a guy whose career value sneaks up on you. He aged very strangely and effectively. When Whitaker first came up as a young player, his batting average came and went, and he had no power. By his mid-20s, he developed a good average and moderate power. Once he found his stroke, he never really lost it.

Thus, he batted .293 with 14 homers in just 84 games at age 38 in his final season. The year before, he batted .301 with 12 homers in 93 games. He was just a pretty good player for a bizarrely long time after his prime.

Also, his usage hurts his popular perception. After 1987, he played over 140 games only once. Manager Sparky Anderson generally sat the lefty-hitting Whitaker against southpaws, so Whitaker was something of a platoon player for nearly a decade. He played in four-fifths of his team’s games, but that still dings his popular perception.

Also, because he lasted so long in this role, memories of his prime fizzled. Instead of benefiting from both parts of his career, they each hurt his candidacy. It’s not fair, but it’s apparently what happened. Whitaker belongs in, and hopefully he’ll go in, but for now he isn’t in.

Alan Trammell

Shortstop Alan Trammell has the best statistical case for enshrinement of the 1980s Tigers.

Want a player with an impressive peak? Check out Trammell’s 1987. He batted .343 with 28 homers and 21 stolen bases (versus only two caught stealings) while playing the diamond’s most important defensive position. He should’ve won the MVP Award that year, but finished second to George Bell in one of the worst votes in baseball awards history.

That was Trammell’s best year, for sure, but he frequently batted over .300 with decent mid-range power throughout his prime. From 1983-88, he batted .303 with 105 homers.

Trammell was an incredibly well-rounded player with no real holes in his game. He had a nice average and decent power, stole over 200 bases in his career, played solid defense, drew his share of walks and was hard to strike out. He wasn’t great at every aspect of the game, but he wasn’t bad at any of them.

Finally, Trammell lasted long enough to tally impressive career numbers. He got over 2,000 hits, including over 600 for extra bases. His 110 OPS+ isn’t terribly impressive on its own, but it’s damn good for a long-lasting shortstop.

Unlike every other player mentioned so far, Trammell didn’t fall off the BBWAA ballot after his first year. He recently completed his 11th turn on the BBWAA ballot and received an all-time personal best of 36.8 percent of the vote. He’s very unlikely ever to go in via the BBWAA but has a good shot with the VC. Generally, good candidates who did that well with the BBWAA get elected by the VC.

He should’ve gone in earlier, but Trammell was always overshadowed by Cal Ripken Jr. While Ripken had 19 consecutive All-Star Game selections, Trammell had only six. Five times, Trammell backed up Ripken in the All-Star Game. The sixth time he was a reserve for Bucky Dent.

As far as I can figure, Trammell is the best position player of the All-Star Game era (1933-onward) never to start in it. (Oddly enough, one of his best competitors for this title is his old teammate, Evans).

The interesting thing for Trammell is how recent the boom in his Hall support has been. He remained stuck at 13-18 percent for eight years but has gone up to 22, 24, and 36 percent ever since.

My hunch is the arrival of Barry Larkin helps Trammell. Normally,a similar player hurts as he competes for votes, but Trammell wasn’t getting that many votes anyway and,more importantly,not only was Larkin widely perceived as a Hall of Famer, but he a clearly similar career to Trammell.

Hopefully Trammell will get in, but for now he isn’t.

Trammell: Currently a bench coach for his old teammate, Kirk Gibson.

Jack Morris

And now for the bizarre, ironic joke in the Tigers' Cooperstown drought: The man who will end it is maybe the fifth- or sixth-best candidate from the 1984 world champions.

Jack Morris was durable. He was damn durable, we have to give him that. And he picked the greatest time possible to hurl his greatest game ever, leading the Twins to a Game Seven, 1-0 10-inning win over the Braves in the 1991 Fall Classic.

But a Hall of Famer? Morris won a lot of games, but that’s in part because he had tremendous aid from his teammates. Those Tigers could hit, and in their prime they also were great at converting batted balls into outs. Teams managed by Sparky Anderson rarely won with great pitching. In Cincinnati and Detroit, he just needed pitchers not to lose so the hitters could win.

Thus, Morris could post 254 wins despite a 3.90 career ERA. He retired with the worst ERA of any 250-game winner. Jamie Moyer has since “surpassed” him, but at least Moyer played in a higher-scoring era, and no one seriously considers him a Hall of Famer.

Morris will go in, though. He’s now well over 60 percent of the vote, and even if he can’t get in via the BBWAA, he’ll go in as soon as the VC gets their hands on him. The Hall loves pitchers with big win totals, and Morris (of course) won more games in the 1980s than anyone.

From the arrival of Evans in 1984 until the departure of Parrish after the 1986 seasons, there were 33 games in which Lemon, Gibson, Evans, Parrish, Whitaker, Trammell, and Morris all appeared in the starting lineup together. The Tigers went 23-10 (.697) in those games. That works out to a 113-49 mark over a full season.

For comparison's sake, in Morris' remaining 72 starts from 1984-86, the Tigers went 43-29 (.597), which is a 97-65 pace. That isn't too much worse than their record with all seven, but in those 72 games you normally had four or five of the star position players in the starting lineup.

Sparky Anderson

One final note. While no player is in Cooperstown from the 1984 Tigers, the team hasn’t been fully skunked by the Hall. Manager Sparky Anderson is in. That makes sense, as he won five pennants and two world titles before ending his career ranked third in managerial wins.

Also, a lot of the world champion squads without any players in Cooperstown had a very well-regarded manager. That makes sense. Only one pre-1984 world champion has no players in Cooperstown: the 1981 Dodgers. Their manager, of course, was Hall of Famer Tommy Lasorda.

Since 1984, the two teams with arguably the worst odds of getting a player into Cooperstown are the 1997 Marlins and 2002 Angels. Their managers, Jim Leyland and Mike Scioscia, respectively, each could make it, however.

So, the Tigers are sort of represented, but they should have some players enshrined as well as their skipper. The issue for Detroit getting its guys into Cooperstown is that they were unusually deep with high-quality position players. These players were either not quite good enough or were underrated when they played, or both.

The oddity is that the overall quality of these many high-quality position players might end up pushing a pitcher into Cooperstown who isn’t as good a candidate as many of them. But at least there will be a 1984 Tiger in Cooperstown. Ideally, Trammell and Whitaker will eventually join Morris there.

History instructor by day, statnerd by night, Chris Jaffe leads one of the most exciting double lives imaginable; with the exception of every other double life possible to imagine. Despite his lack of comic-book-hero-worthiness, Chris enjoys farting around with this stuff. His new book, Evaluating Baseball's Managers is available for order. Chris welcomes responses to his articles via e-mail.

Proud Member of DIBS

Proud Member of DIBS

1 Comments:

Wow, great article. Whatever happens with the HOF, why can't the Tigers do something for them? Does a player have to be a HOFer to have their numbers retired or have a statue (love to see Tram and Lou 'turning two'). They dropped the ball with Sparky, but they don't have to with these other Tigers legends, HOFers or not. I was disappointed the organization did so little to honor Mark 'The Bird' Fidrych after his un-timely death (granted he might not get his number retired or a statue, but they could have at least made a patch, or something.) The Tigers need to make things right themselves, and mayber others will take notice.

--Mike

http://burrilltalksbaseball.mlblogs.com

Post a Comment

<< Home